Headaches That Are Medical Emergencies

Posted on August 05 2023,

This post is for educational purposes only and may contain errors. Please talk to your neurologist or healthcare professional. There are many pathologies that may cause headache so this is not an all-encompassing list.

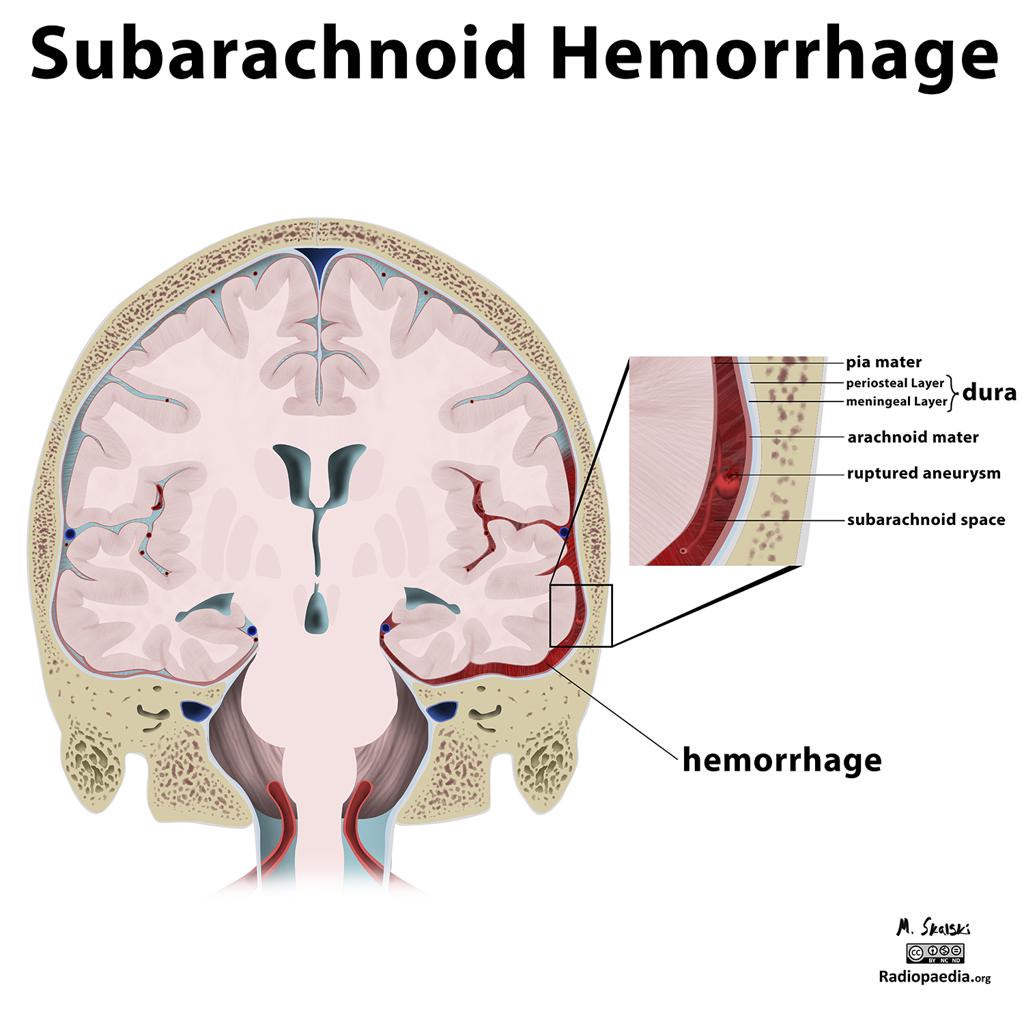

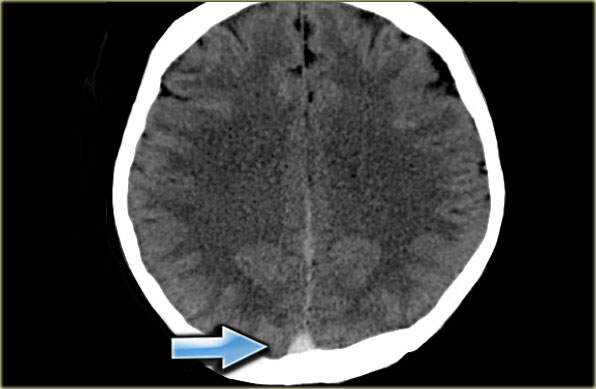

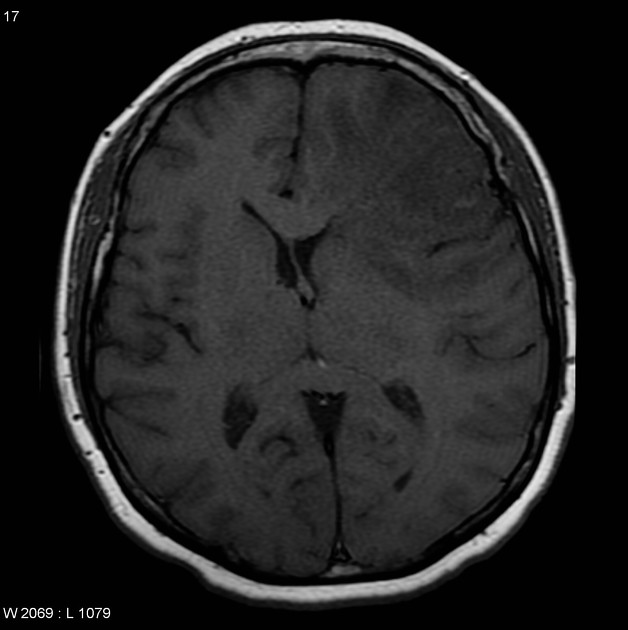

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is an uncommon type of stroke characterized by bleeding into the subarachnoid space surrounding the brain, leading to brain injury and high rates of disability and mortality. In the absence of trauma, 85% of cases involve a rupture of an intracranial aneurysm.

- Sudden onset of severe headache is reported in 70% of cases. Pain is typically described as the "worst headache of my life."

- Neck stiffness and pain are common. Nausea, vomiting, photophobia, transient loss of consciousness, seizures may occur.

- Physical findings include meningismus. May see retinal or subhyaloid hemorrhages on fundoscopy.

- Noncontrast head CT is the primary diagnostic tool. Lumbar puncture is essential if CT is negative or equivocal.

- Immediate neurosurgery consultation is required once SAH is diagnosed. Priorities are preventing rebleeding and cerebral vasospasm.

SAH. Image source: Radiopaedia

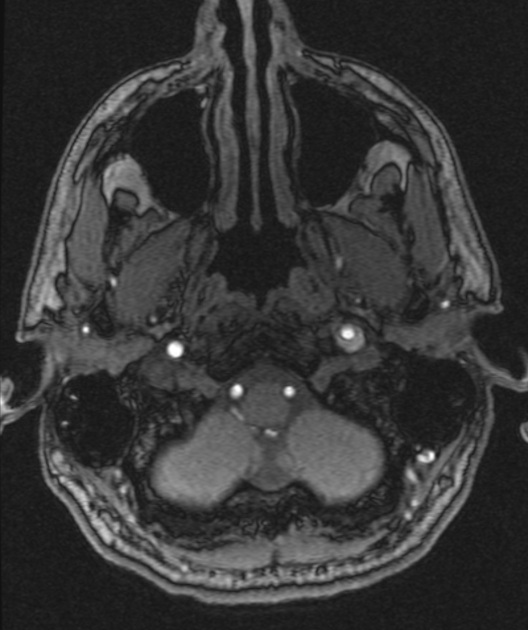

Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndromes (RCVS)

- RCVS presents with sudden, severe "thunderclap" headaches that recur over days to weeks. Headaches are often triggered by activities like exertion, sexual activity, bathing, Valsalva maneuvers.

- Associated conditions include pregnancy, migraine, vasoactive drug use, cervical artery dissection. The underlying pathogenesis is unclear.

- RCVS refers to a group of conditions characterized by recurrent headaches and reversible multifocal narrowing of cerebral arteries, not just one condition or entity. It is a clinical AND radiologic condition.

- Noncontrast head CT may show cerebral infarctions. CT or MR angiography reveals diffuse segmental narrowing of intracranial arteries.

- May progress to ischemic strokes, brain edema, seizures, visual disturbances, but rare.

- Calcium channel blockers may relieve symptoms, but do not prevent complications such as ischemic stroke.

- Blood pressure support is necessary.

- Prognosis is generally good, with most patients recovering fully over days to weeks.

- Recurrence of RCVS is uncommon. No genetic implications are known.

Angiogram showing vasoconstriction in RCVS. Image source: Radiopaedia

Cervical Artery Dissection

- Usually occurs when a small tear develops in one of the inner layers of the artery wall, creating a pocket where blood can pool.

- Dissections most commonly involve the internal carotid arteries in the neck or the vertebral arteries that supply the brain.

- Often preceded by trivial neck trauma (eg, yoga, chiropractic manipulation, coughing, sneezing).

- Accounts for up to 25% of ischemic strokes in young and middle-aged people.

- Unilateral head/neck pain is common. May have Horner's syndrome, pulsatile tinnitus.

- Physical findings include: Cranial neuropathies, ipsilateral Horner's syndrome, nystagmus. Focal neurological deficits in up to 60% of patients.

- Non-contrast head CT followed by CT angiography (CTA) or MR angiography (MRA) of the head and neck is recommended.

- Anticoagulation is standard treatment to prevent thromboembolic complications.

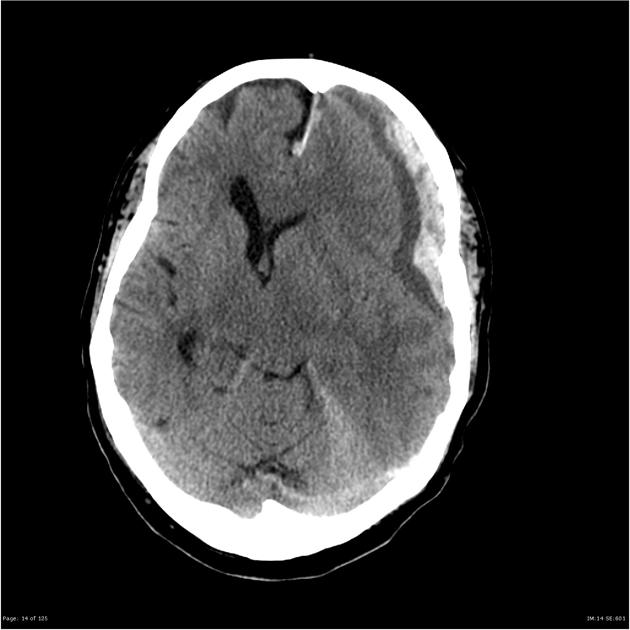

Cerebral Vein/Dural Sinus Thrombosis

- Rare form of stroke. Thrombosis of the cerebral veins and/or dural sinus.

- Highly variable presentation. Risk factors include hypercoagulable states, pregnancy, infection, malignancy.

- Suspect in younger patients less than 50 years old with signs of intracranial hypertension, new seizure, and/or unexplained focal neurologic abnormalities.

- Headache often gradual in onset. Neurologic deficits atypical of arterial distribution. Seizures may occur.

- Papilledema strongly suggests the diagnosis.

- CT or MRI useful for initial evaluation but does not rule out if normal.

- CTV/MRV is the next step if CT/MRI are normal.

- Anticoagulation is the cornerstone of treatment, along with treatment of any underlying cause.

Direct visualization of a clot in the cerebral veins on a non enhanced CT scan is known as the dense clot sign. It is seen in only one third of cases. Source: radiologyassistant

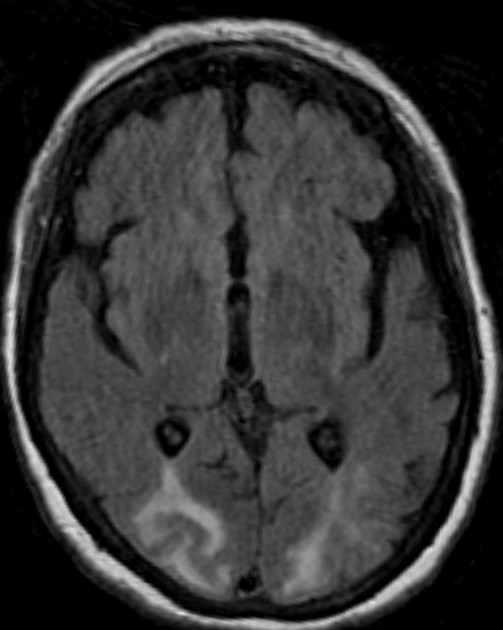

Hypertensive Encephalopathy/Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES)

- Clinical and neuroradiologic syndrome which involves an acute onset of neurologic symptoms with patchy areas of vasogenic edema on imaging.

- Usually caused by an acute increase in blood pressure. May also be caused by severe metabolic abnormalities or medications.

- Symptoms include headaches, visual disturbances, seizures, and mental status changes. Symptom severity can range from mild to severe.

- Findings include papilledema, retinal hemorrhages, visual field defects. MRI shows subcortical and cortical edema.

- Correcting blood pressure is critical. Treat seizures per standard seizure protocols.

- Reversible in 70-90% of patients with prompt diagnosis and treatment. Residual side effects such as epilepsy or motor deficits may persist in severe cases.

MRI in PRES showing high signal on FLAIR. Image source: Radiopaedia

MRI in PRES showing high signal on FLAIR. Image source: Radiopaedia

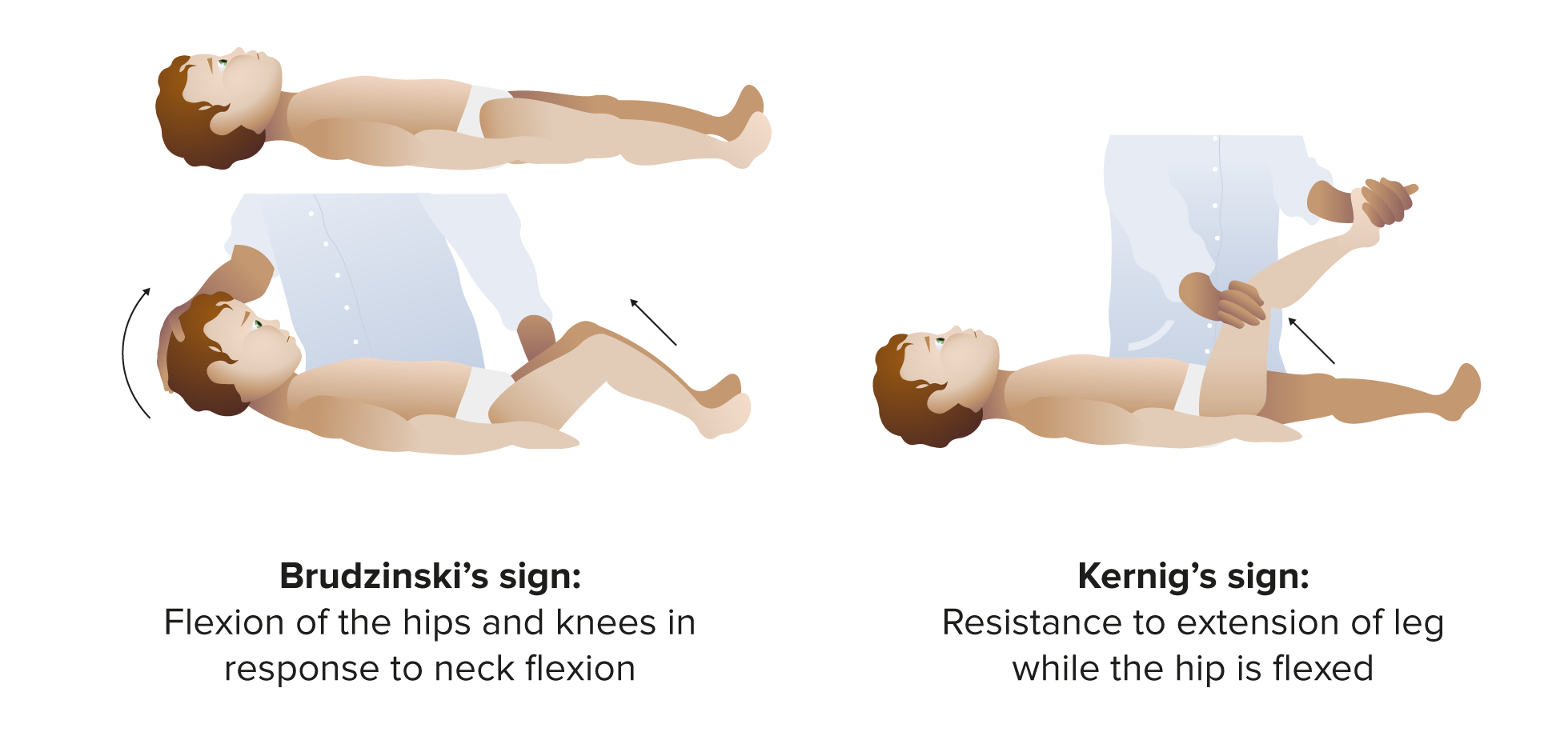

Meningitis/Encephalitis

- Bacterial meningitis classically presents with fever, nuchal rigidity, and altered mental status.

- Physical findings include meningismus and signs of increased intracranial pressure. Petechial rash may be seen.

- Perform blood cultures, give antibiotics, then do noncontrast head CT followed by lumbar puncture if no contraindications.

- Viral encephalitis may present with fever, seizures, focal neurological deficits. Head CT or MRI can aid diagnosis.

- Brudzinski sign - involuntary flexion of the hip and knee when the neck is passively flexed. Indicates meningeal irritation.

- Kernig sign - pain and resistance to knee extension when the hip is flexed to 90 degrees. Also indicates meningeal irritation.

- Presence of either sign increases likelihood of meningitis but definitive diagnosis requires CSF analysis.

- Absence of signs does not rule out meningitis. Both have low sensitivity overall.

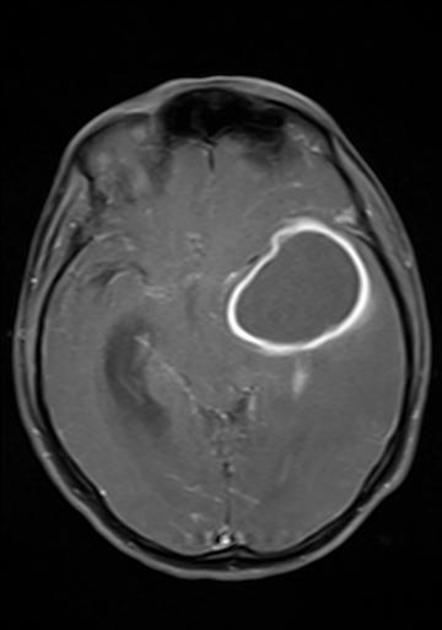

Brain Abscess

- Focal collection of purulent material in the brain parenchyma.

- May be caused by fungi, parasites, or bacteria (most cases).

- History of recent infection (usually sinusitis, mastoiditis, or a dental infection), immunocompromised state, IV drug use.

- Gradual onset headache, fever, and neurological deficits.

- Brain imaging demonstrates ring-enhancing lesion(s). Lumbar puncture shows elevated opening pressure.

- IV antibiotics and neurosurgical drainage and decompression are mainstays of treatment.

Brain abscess on MRI. Image source: Radiopaedia

Brain Tumor

- Steady progression of headaches, worsened by Valsalva/coughing. May be associated with nausea and vomiting.

- Neurological deficits such as visual changes, weakness, sensory loss depending on location.

- MRI with contrast is diagnostic imaging modality of choice.

- Neurosurgical resection, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy are treatment options depending on tumor type.

Glioblastoma on MRI. Image source: Radiopaedia

Intracranial or Extra-Axial (subdural or epidural) Hematoma

- Often follows recent head trauma, even minor injuries. Anticoagulant use increases risk.

- Gradual decline in mental status, vomiting without another explainable cause.

- Absence of symptoms is not a reason to dismiss. “Lucid intervals” between time of injury and symptom onset can last from 15 minutes to 4 days seen in subdural hematoma.

- Posterior fossa lesions may cause cranial neuropathies, ataxia.

- Emergent head CT shows concave (subdural hematoma) or convex-shaped (epidural hematoma) hyperdense lesion with mass effect.

- Neurosurgical evacuation is required, but conservative management is an option for a subset of patients.

Epidural hematoma on head CT. Image source: Radiopaedia

Subdural hematoma on head CT. Image source: Radiopaedia

Colloid Cyst of Third Ventricle

- Rare so evidence is limited.

- Intermittent positional headaches that resolve when lying down. Confusion, syncope may occur.

- Obstructive hydrocephalus on brain imaging.

- Neurosurgical resection via transcortical or endoscopic approach.

Colloid cyst at foramen of Monro on MRI. Image source: Radiopaedia

Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension

- Characterized by an elevated intracranial pressure with no established cause.

- Daily headaches with transient visual darkening, and pulsatile tinnitus.

- Seen in obese women of childbearing age.

- Papilledema is hallmark finding. Sixth cranial nerve palsy may be seen, but normal neurological findings otherwise.

- If no papilledema, sixth cranial nerve palsy required for diagnosis.

- MRI and lumbar puncture confirm diagnosis. Acetazolamide and weight loss are cornerstones of treatment.

- Treatment includes weight loss, medical therapy, procedures if imminent threat to vision, and headache management.

Papilledema in IIH. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

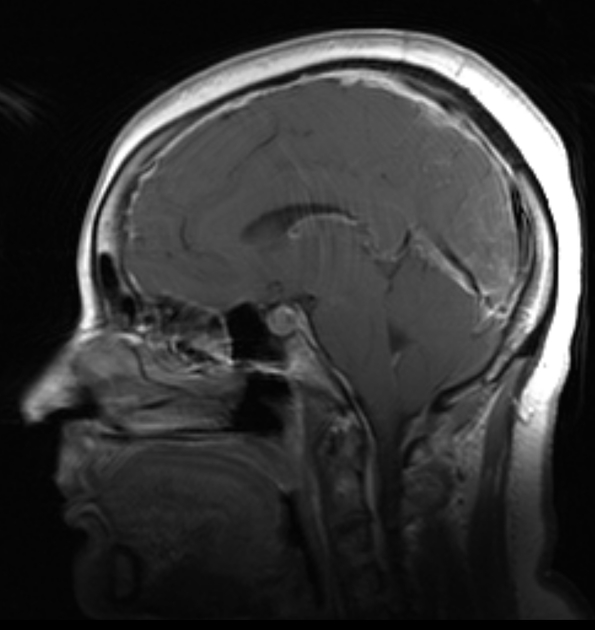

Spontaneous Intracranial Hypotension

- Uncommon condition due to low cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) volume and pressure.

- Usually caused by a spine pathology that leads to a spontaneous CSF leak.

- Postural headache relieved by lying flat (orthostatic headache). Associated with nausea, back and/or neck pain, tinnitus.

- Brain and spinal MRI with contrast necessary.

- First-line approach is conservative management and epidural blood patches are a second-line approach.

MRI showing smooth pachymeningeal enhancement, effacement of cortical sulci (more than would be expected for a person of this age), sagging cerebellar tonsils, and a plump/full pituitary gland. These findings are consistent with intracranial hypotension. Image source: Radiopaedia

Acute Angle-Closure Glaucoma

- Narrowing or closure of the anterior chamber angle that prevents drainage of the aqueous humor resulting in increased intraocular pressure and possible damage to the optic nerve.

- Unilateral severe eye pain, eye redness, headache, nausea, vomiting, blurred or loss of vision.

- Gonioscopy necessary.

- Physical findings include corneal edema, fixed mid-dilated pupil, elevated intraocular pressure.

- Immediate ophthalmology consultation necessary.

Appearance of AACG. Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Giant Cell Arteritis (Specifically temporal arteritis)

- Vasculitis involving large and medium-sized arteries that is a medical emergency due to risk of vision loss.

- New headache in patient over age 50. May have jaw claudication, scalp tenderness over temporal arteries.

- ESR and CRP are elevated. Temporal artery biopsy is diagnostic.

- High dose glucocorticoids are mainstay of treatment and started immediately (even if only suspected due to risk of vision loss).

GCA-positive temporal artery biopsy. Source: Journal of Ophthalmic & Vision Research

Carbon Monoxide (CO) Toxicity

- Headache in context of CO exposure. Leading cause of death from unintentional poisoning in the United States.

- Risk factors include smoke inhalation, certain heating/cooking devices, motor vehicle fumes, exposure to methylene chloride.

- Manifests as confusion, lethargy, nausea, cherry-red skin. CO-oximetry shows elevated carboxyhemoglobin level (a pulse oximetry will show normal oxygenation). Low or normal levels do not rule out CO toxicity.

- Arterial blood gas (may also be done with venous blood gas, which is less painful and invasive) is the definitive test for CO toxicity.

- Give 100% oxygen and evacuate from site of exposure immediately. Hyperbaric oxygen may be used in severe toxicity.

Cherry red skin from CO poisoning. Source: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63895-9_16

Mon, Nov 17, 25

Migraine Research - During the week of my absence.

Migraine Research - During the week of my absence. The Association Between Insomnia and Migraine Disability and Quality of Life This study examined how insomnia severity relates to migraine disability...

Read MoreSat, Nov 01, 25

Anti-CGRP Monoclonal Antibody Migraine Treatment: Super-Responders and Absolute Responders and When to Expect Results

Anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies achieved 70% super-response and 23% complete migraine freedom in a one-year study. Most dramatic improvements occurred after 6 months of treatment. For patients with chronic or high-frequency...

Read MoreAll Non-Invasive Neuromodulation Devices for Migraine Treatment

Wondering if migraine devices actually work? This guide breaks down the latest evidence on non-invasive neuromodulation devices like Cefaly, Nerivio, and gammaCore. Learn which devices have solid research backing them,...

Read More