Migraine: The Missing Component of the Atopic March

Posted on November 24 2023,

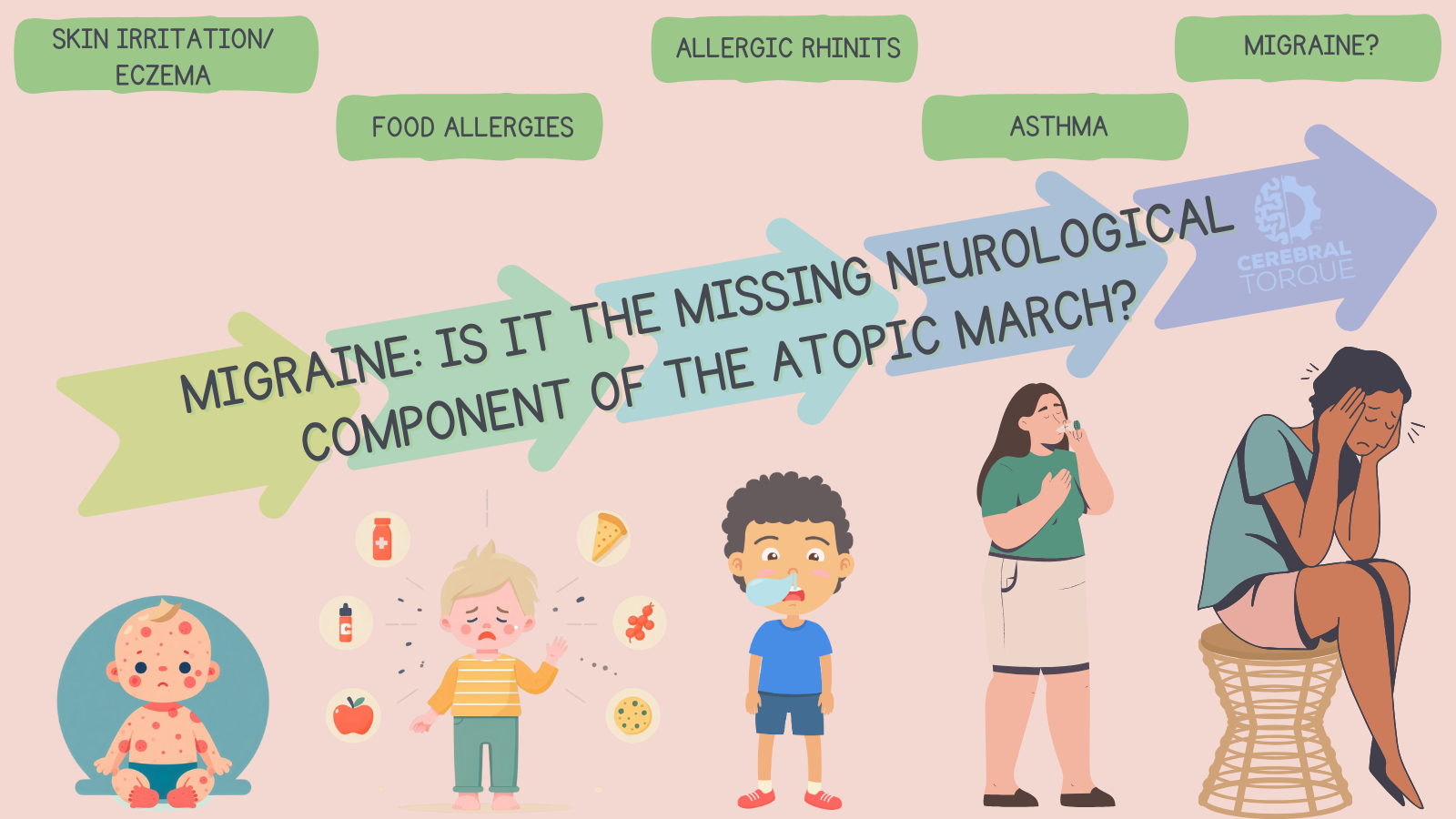

The atopic march refers to the progression of allergic diseases from childhood into adulthood. First described as a triad of atopic dermatitis (eczema), asthma, and allergic rhinitis (hay fever), I propose that accumulating evidence suggests migraine also belongs as part of an atopic TETRAD and, at the very least, a component of the atopic march.

In the traditional understanding of the atopic march, it begins with eczema followed by allergic rhinitis and asthma in later childhood. We now recognize that natural course of this phenomenon may begin with eczema (or even dry skin before this) then food allergies then allergic rhinitis, and, finally, asthma.

While each condition appears sequentially from childhood to adulthood, they don’t have to. This is not a path of destiny, but rather tendencies or likelihoods of one disease progressing to the next. There are many factors involved that modulate one’s tendency to progress to the next disease such as disease severity (e.g., mild eczema may not progress to other atopies, but severe eczema is more likely to), environmental triggers, genetic risk factors (e.g., if there is no filaggrin mutation, the development of eczema may not occur), etc.

I will show that these four diseases are connected by shared epidemiological trends, common genetic risk factors, immunological mechanisms, and modulating factors.

If true, the recognition of migraine as part of this “tetrad” will allow for better understanding and possibly prevention, screening and earlier diagnosis, and overall management of migraine.

Furthermore, I hope to provide encouraging reasons why those that practice in allergy and immunology must refer their patients to a neurologist at the first sign of a headache.

Epidemiological Links

Population-based studies reveal increased migraine prevalence in patients with asthma and allergic rhinitis compared to the general population, with up to 50% of patients with migraine having comorbid allergic rhinitis.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3809225/

This association between allergic rhinitis and migraine has also been shown to be stronger in patients over 40 years old as can be seen in this cross-sectional comparative study:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3634285/

This further adds evidence to the theory that migraine is part of the atopic march as the relationship between allergic rhinitis and migraine becomes more prevalent with age.

A meta-analysis found a significant association between migraine and asthma. In fact, there was a bidirectional relationship where migraine is a risk factor for developing asthma, and asthma is also a risk factor for developing migraine. This emphasizes that there are similar underlying pathophysiological mechanisms involved- likely environmental, inflammatory, and immune dysfunction.

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2020.609528/full

This isn’t new in the realm of medicine or neurology. It has now been discovered that a virus, specifically Epstein-Barr virus, is the cause of multiple sclerosis- a progressive neurological disease.

Interestingly, in a longitudinal, observational cohort study, the authors studied whether asthma is a risk factor for chronic migraine among those that already have episodic migraine. The results found that asthma is a risk factor for chronic migraine in those that have episodic migraine, and the risk was highest among those with the greatest number of asthma symptoms.

https://headachejournal.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/head.12731

This is very similar to studies that show that the worse eczema symptoms are, the more likely a patient is to develop asthma. Now we know that the worse the asthma is, the more likely a patient is to develop chronic migraine. Dare we say migraine is part of the atopic march? Let’s keep going.

A study of over 400,000 US children found that eczema increased the odds of headaches. The association was strongest for severe eczema, but even mild and moderate eczema conferred increased headache risk compared to children without eczema. Eczema was associated with higher headache prevalence at all ages during childhood. When combined with other atopic diseases like asthma, allergic rhinitis, or food allergy, the association with headaches became even stronger.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26329510/

Multiple studies show positive correlations between migraine frequency and severity and allergen specific IgE levels. Higher total IgE levels correlate with more frequent monthly headaches. Patients with both allergic rhinitis and asthma have greater migraine prevalence than those with asthma alone, suggesting an additive effect.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3972598/

A cross-sectional study found that adults with atopic dermatitis were 89% more likely to have a diagnosis of migraine even after controlling for common comorbidities. This demonstrates the association continues into adulthood.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36669173

Genetic Factors

Specific genetic variants in signaling molecules like tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) heighten susceptibility to both migraine and atopic diseases including asthma, eczema, and allergic rhinitis. TNF-α drives transcription of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) while broadly regulating inflammation. Meanwhile, polymorphisms in leukotriene C4 synthase genes influence cysteinyl leukotriene-mediated allergy and migraine susceptibility.

TNF-α in migraine:

https://www.spandidos-publications.com/10.3892/etm.2012.533

TNF-α in eczema:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1793658/

TNF-α in allergic rhinitis:

https://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(03)01369-1

TNF-α in asthma:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17475560/

Immunological Mechanisms

Migraine attacks involve mast cell activation, eosinophil accumulation, and release of cytokines, which stimulate downstream essential components of allergic inflammation.

Migraine patients experience elevated plasma histamine levels during attacks and during interictal periods suggesting mast cell activation. Allergic rhinitis, asthma, and food allergies are histamine-driven conditions. However, it’s important to note that, in general, antihistamines are not the best at treating migraine even though IV diphenhydramine (Benadryl) is given in the emergency department (if you read my article on migraine cocktail, you’ll remember that the American Headache Society classifies Benadryl as level C and, thus, recommends against its use.

https://www.cerebraltorque.com/blogs/migrainescience/migraine-cocktail

The lack of a theoretically possible treatment not being effective does not negate the underlying pathophysiology. We have seen this before with pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide (PACAP) antagonists. PACAP is important in migraine pathophysiology, but the treatment targeting this neuropeptide has not been effective.

Speaking of PACAP, it has also been shown to induce mast cell degranulation.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0333102412439354

Mast cell activation and degranulation can directly stimulate trigeminal nerves through release of histamine, leukotrienes, and prostaglandins. And, as evidenced in the linked study above, increased mast cell prevalence is seen in dura mater from migraine patients.

Therefore, given the pro-inflammatory nature of mast cell activation and their occurrence in the dura mater, it is sensible to assume that the same pathophysiological processes that underly atopic diseases also underly migraine and may even lead to the development of migraine.

Modulating Factors

Allergens may directly activate trigeminal nerves through inflammatory mediators like histamine and leukotrienes released during mast cell degranulation. Th2 inflammation is central to both migraine and atopic disorders.

Cytokines like TNF-alpha, IL-1 beta, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 are increased during migraine attacks and play key roles in allergic reactions. Dysfunctional regulation of these cytokines could precipitate both migraine and atopic symptoms.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5216169/

Smooth muscle dysfunction in cerebral blood vessels and bronchial airways may also connect migraine with asthma via an underlying pathophysiology. Although, as we know, migraine is no longer considered a vascular disease, it may still be a component in this mystery.

The atopic state itself may promote sensitization to triggers that provoke migraine attacks. Cross-reactivity between environmental allergens and migraine-associated antigens could stimulate inflammatory pathways. IgE-mediated chronic allergic inflammation may lower the trigger threshold for migraine headaches and cause more severe attacks.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3972598

Clinical Implications

The epidemiological, genetic, immunological, and modulating factors provide compelling evidence to expand the atopic march from a triad to a tetrad by including migraine.

Recognition of migraine as part of the atopic march has significant implications for early diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Patients with atopic disorders may benefit from more aggressive migraine screening. Allergists must be aware of this connection and refer to a neurologist immediately if a patient has atopy and is complaining of headache.

We already have evidence that children who had been treated long-term with inhaled/nasal corticosteroids or antihistamines (treatment for atopic diseases) had a lower risk of migraine compared to untreated children.

https://headachejournal.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/head.13032

Targeting shared inflammatory pathways between the traditional atopic diseases and migraine may also be a new treatment avenue.

We can also start inquiring about prevention. Currently, we do have prevention strategies for patients at risk for developing allergic diseases. These include avoiding tobacco smoke, pollution, certain viruses like RSV, dust mites, and promoting breastfeeding or even the application of moisturizer (although there are two conflicting studies on this).

https://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(14)01118-X/fulltext

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(19)32984-8/fulltext

Ultimately, elucidating the mechanisms linking migraine with atopic disease will open new therapies benefiting millions of patients. Further research on the mechanisms linking migraine and atopic disease is warranted, as recognizing migraine as an atopic comorbidity could significantly impact prevention and treatment approaches.

Wed, Jan 14, 26

New Emergency Department Migraine Treatment Guidelines

The American Headache Society (AHS) has released its 2025 guideline update for the acute treatment of migraine in adults presenting to the emergency department. This update, published in Headache in...

Read MoreSun, Jan 04, 26

Long-Term Safety of Anti-CGRP Monoclonal Antibodies

A comprehensive meta-analysis of over 4,300 patients reveals that erenumab, galcanezumab, fremanezumab, and eptinezumab maintain good tolerability beyond 12 months. Only 3% of patients stopped treatment due to adverse events,...

Read MoreThu, Jan 01, 26

Alternate Nostril Breathing Protocol for Migraine

Alternate nostril breathing is a simple yogic technique that's showing real promise for migraine prevention. Unlike acute treatments, this practice builds nervous system resilience over time - making attacks less...

Read More